Press

Resource Center

CENTER STAGE:

Maria Lind in conversation with Trevor Paglen

Focusing on Art's imaginative qualities, social impact and active relationship to the future,

the CENTER STAGE series directs our attention to the question:

WHAT DOES ART DO?

Maria Lind:

An overarching question for the upcoming Gwangju Biennial, which I’m curating and you’re invited to participate in, is, "What does art do?" This is a notoriously difficult question, but one which nevertheless needs to be asked, particularly in times when infrastructural concerns tend to dominate any discussion involving art.

I am thinking about the current (understandable) preoccupation with the effects of the commercial art market and populist programming in mainstream art institutions, as well as the worries among small- and medium-size agents regarding mere institutional survival. Somewhere along the way, art itself seems to have been forgotten. Thinking about your recent exhibition at Metro Pictures in NYC, and particularly your underwater photographs of cables that enable all kinds of communication, including surveillance, I wonder: what would you say these photographs do?

Trevor Paglen:

I’m going to push back against the idea of art having to “do” anything at all. If there’s any way that art can point towards freedom, it’s through the fact that it doesn’t have to participate in an economy of use. Having said that, I’m not so naive as to think this is actually radical way, because artworks can only function in particular economies, whether it’s an economy of luxury goods, of biennials and urban development or of academia, state-sponsored “community building” and social work.

So with that disclaimer, what I want out of art is very modest. I want things that help us see the historical moment we’re living in, and I want things that give us a glimpse into how that historical moment might be different. I think that artworks can serve important functions in a society: they can give people permission to look at something or think about something in new ways.

Maria Lind:

Point taken, although my interests lay less in a utilitarian understanding of art than in the fact that art “does” something, regardless: even not “doing anything,” being seemingly “useless,” is a sort of function, one that can be extremely important in times of imposed efficiency.

Furthermore, it’s often more interesting to look at concrete cases of what art works do—for example, how your aforementioned series of photographs grant a “permission” to look at something particular, parts of the palpably physical infrastructure of the globalizing control systems, in unfamiliar ways.

That being said, you have combined some these photographs with a new series of collages based on nautical maps. Here the activity of mapping comes to the fore, materially speaking. Can you talk a bit about your method of mapping and your relationship to cultural geography?

Trevor Paglen:

For a long time, I’ve been a big critic of cartography and “mapping” projects, so it feels pretty awkward to be using a cartographic vocabulary in some of these works. These pieces are looking at the relationship between the “dematerialized” metaphors we use to describe the Internet and its corollary, which is mass surveillance. We use words and metaphors like “the cloud” and “cyberspace” that are literally mystifying metaphors.

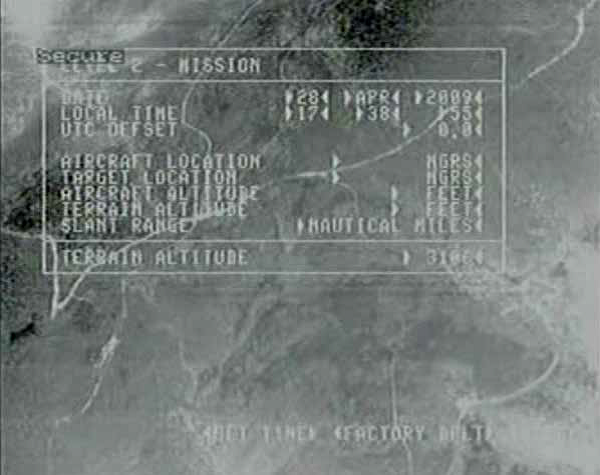

Each work in the project you’re referring to is a diptych in which a photograph is coupled with a collage of found materials on top of a nautical chart. Those photographs, which don’t provide any visual evidence of the “content” of the photograph (NSA mass surveillance) are paired with collages made from nautical charts, documents from the Snowden archive and many other sources, all of which speak to the activities and infrastructures that are invisibly present in the photograph. In those diptychs, I’m trying to develop highly specific “re-materialized” views of global telecommunications and mass surveillance, while at the same time showing how they’re not easily visible in the landscapes around us.

They’re not meant to be explanatory or didactic at all; you could look at them all day and wouldn’t really be able to make sense of them. But I’m not trying to be obfuscating, either. I’m trying to develop a series of metaphors, a vocabulary of mass surveillance based in materiality, as a counterpoint to metaphors like “the cloud.” As far as human geography goes, they’re not an exercise in human geography, and really don’t have much to do with it. They’re much more relevant to the landscape tradition.

Maria Lind:

One of your latest bodies of work deals with contemporary production and the reception of images. It involves algorithmically produced images, many of which will never be viewed by humans, only by machines. How do you enter this terrain, and what are you expecting in terms of results?

Trevor Plagen:

For a number of years now, I’ve been thinking about the fact that visuality is increasingly becoming post-human. What I mean is that sitting here in 2016, most of the images in the world are made by machines for other machines, with humans rarely in the loop. I’m talking about everything from algorithmic object recognition and facial recognition as conducted by things like Facebook’s “Deep Face” software, to more simplistic systems like Vigilant Solutions’ mobile license plate reading project.

We’re seeing human vision and visual culture quickly becoming an anomaly within a much larger landscape of machine vision and machine learning. What’s more, the traditional theoretical frameworks we’ve developed to think about visuality (semiotics, etc.) really are of almost no help in understanding the post-human visual landscape.

Finally, much of this post-human visual landscape is invisible humans—as a matter of efficiency, machine-readable images don’t have to translate color, value or edges into human- readable images. As someone who’s concerned about visuality, I’m obviously interested in this. I’ve been doing some writing about it, and have been trying to work on this visually for a number of years, but it’s really hard because it’s highly technical and largely invisible to human eyes, so you actually have to build tools that translate machine visuality into forms of seeing that are accessible to the human eye. Some of the fruits of this work are just starting to come out, and I’m happy to be able to start sharing some of it soon.

Trevor Plagen (American, b. 1974) is an artist who lives and works in Berlin, Germany. He is represented by Metro Pictures, New York, and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco. His work is currently on view in the group exhibitions “Political Populism” at Kunsthalle Wien through 7 February and “Electronic Superhighway” at Whitechapel Gallery, London, through 15 May.

Maria Lind is the Director of the Tensta Konsthall, Stockholm and an independent curator and writer. She was appointed Artistic Director for the 2016 Gwangju Biennale, to be held from 2 September–6 November.

Images: Untitled (Reaper Drone), 2010. Courtesy of the artist; Metro Pictures, New York; and Altman Siegel, San Francisco; Drone Vision (Still), 2010. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Zander Gallery, Clogne; Symbology, Vol. 1 (detail), 2006. Courtesy of the artist and Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne; Next page top: Earth Orbit, 2012, from “The Last Pictures Disc" series.

http://kaleidoscope.media/kaleidoscope-asia-3/